Show Notes:

Aspiring novelist Ben Hess explores writing from the deep end of loss, grief, and uncertainty with teachers and authors Tom Barbash, Gary Ferguson, Alan Heathcock, Pam Houston, and Josh Weil.

Links:

- Writing By Writers - http://writingxwriters.org

- Tom Barbash - https://www.facebook.com/Tom-Barbash-1403861426501638/timeline/

- Pam Houston - http://pamhouston.net

- Alan Heathcock - http://alanheathcock.com

- Gary Ferguson - http://wildwords.net

- Josh Weil - http://www.joshweil.com

- NPR Fresh Air - Terry Gross interview with memoirist Mary Karr

Produced & Hosted By @BenHess

Story Geometry Ep3 - The Deep End

Ben Hess: Welcome to Story Geometry, the podcast plotting insights on the craft and community of writing and storytelling from leading published authors of our day with a razor sharp #2 pencil. I’m your host, aspiring novelist Ben Hess, and this is Episode Three - The Deep End. My partner in literary exploration throughout Season One is Writing By Writers founded by award winning teacher and writer Pam Houston and nonprofit executive Karen Nelson. They’d love to have you stop by and explore their 2016 workshops and adventures - visit writing x writers dot org. So it’s mid September now, which historically signifies a change in season from Summer to Fall, and the beginning of another school year. But in recent times, the 11th casts a haunting shadow on the calendar

Tom Barbash: When 9/11 happened … this firm Cantor Fitzgerald ... lost over 658 members, you know, people would had worked there - this company of a thousand people and it was sorta epicenter of the tragedy.

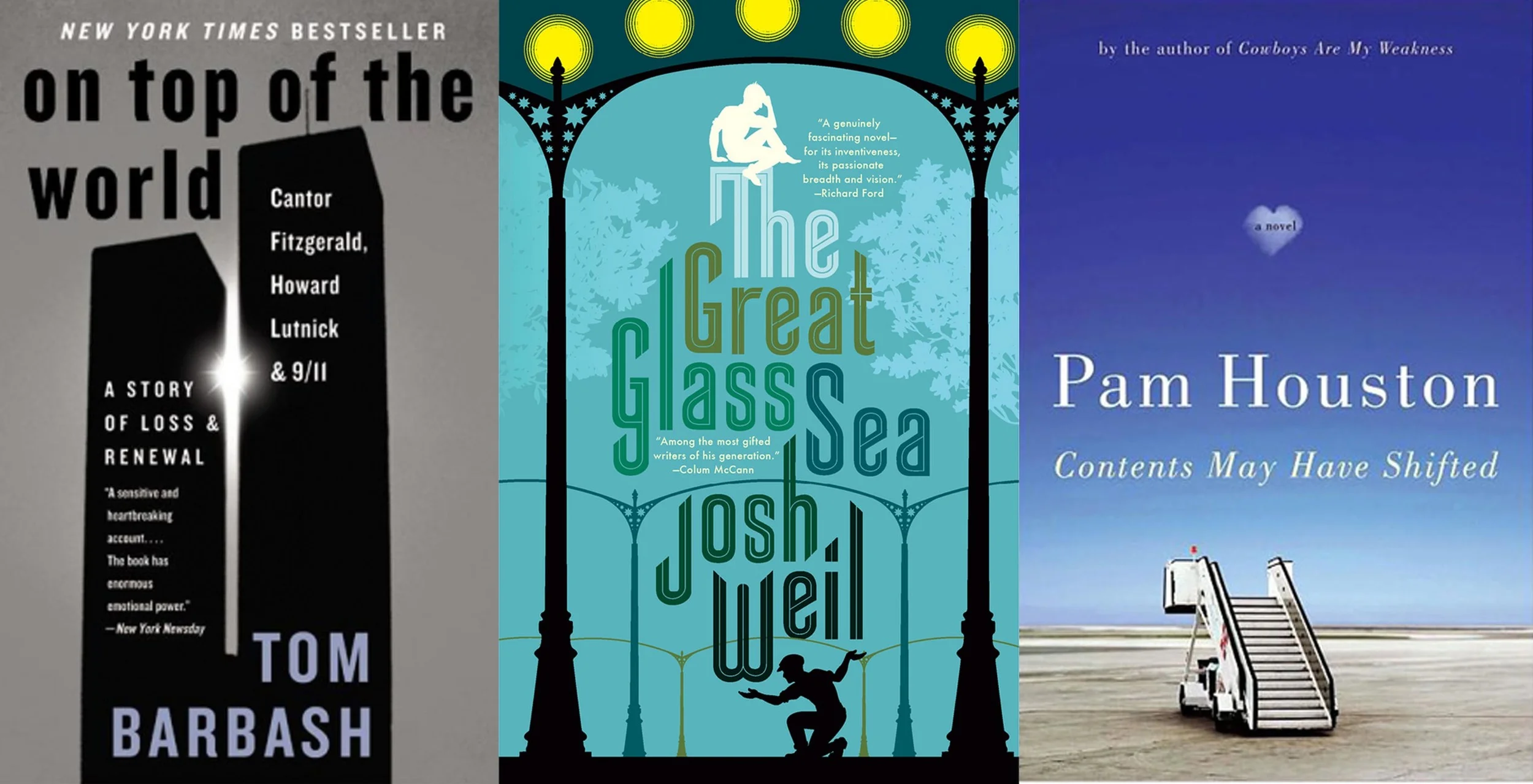

BH: This is Tom Barbash, author of the award-winning collection Stay Up With Me, the novel The Last Good Chance and the New York Times bestseller, On Top of the World: Cantor Fitzgerald, Howard Lutnick, & 9/11: A Story of Loss & Renewal. Tom was thrown into the literary deep end days after 9/11 while navigating personal grief and loss.

TB: The chairman, Howard Lutnick of Cantor Fitzgerald -- sort’ve the New York Stock Exchange for bonds – he was on my tennis team and a friend of mine, I actually knew him before college from tennis tournaments … I was away traveling in Spain and he was on television crying, he was the sort’ve the face of the tragedy …

Female News Anchor: Cantor Fitzgerald sort’ve symbolizes the devastation of the terrorist attack.

Howard Lutnick (news excerpt): We have to make our company … be able to take care … of my 700 families.

TB: Originally we were going to write something together and then he was too caught up in saving the company and doing whatever you need to do to work around the clock, to just kind of stay afloat and I ended up with this incredible responsibility of writing the story about grief, a story about this company trying to reboot within 48 hours to stay viable and then the media crush around them which which was a sort of story in which they got vilified and then sorta pulled out of that and it was quite surreal and um with a short deadline so it sort of reporting around the clock writing around the clock and I lost four friends in the tragedy and was going to funerals so I was sort of being a friend and being a writer secondarily and then off then I had to really start to kick it in.

BH: While Tom grappled with the daunting task of feverishly reporting and writing a personal account of the worst terrorist attack ever on American soil, naturalist and creative nonfiction writer Gary Ferguson used writing to navigate the grief of losing his wife Jane in a canoeing accident. The result is his memoir The Carry Home: Lessons from the American Wilderness. We chatted on a spring morning in stunning Boulder, Colorado.

You write so eloquently about your grief and what you went through, at what stage of the process did you realize you were going to write, or were you writing pieces of this all along the journey?

Gary Ferguson: Well, the first I’d say almost two years after the accident I journaled and that was really a self-indulgent exercise to pour out onto the page all the emotional upheaval that was going on, the sadness, the sense of betrayal, all of that, came down in journal fashion. After a couple of years I asked myself the question quite blatantly literally, is this a story, the story of how nature can inform people’s lives and actually inform the difficult process of healing after a major loss, is that a story that other people would benefit from, is it a story that Jane would want to tell, and I decided it was, at that point then there comes a great shift when you’re telling for public consumption.

BH: Was there any kind of issue about publication or concerned about moving the book from idea to actual book?

GF: Normally I would run out an idea with my agent, I had a time to see if she thought it was marketable. This was not that way. I was going to write this book no matter what. And so I spent the next six years writing the book assuming that ultimately it would see publication because it would draw out something that was worthwhile, and as difficult as it was, it pushed me in a way, from a craft perspective alone, not only emotionally, but it pushed me in a craft perspective way that I think I’m going to lean on and use for every book that follows.

BH: While Gary painstakingly, eloquently crafted his memoir, Tom was under very different constraints:

TB: It’s called the terrible word, given what happened on 9/11 but in the business they call it a crash book meaning you you do it quickly.

BH: So feeling pressure of writing about this massive event, Tom leaned on his training as a journalist to craft story, just as Charles Dickens, Edgar Allan Poe, and Ernest Hemingway did before.

TB: I came in having a background as a journalist but also being a novelist and that helped me a lot. … I jumped right into page 175, you know, of a pretty sad dramatic novel and I there are lots of moving pieces in the same way I had just moved from from a novel with lots of moving pieces, I could see it …

BH: Tom’s referring to his novel The Last Good Chance that he had just finished in August 2001 which had prompted the celebratory trip to Spain. But with On Top of the World ...

TB: I could see the story of my friend as a character, I can see you know with his interesting past: his parents who died in high school and his freshman year and college how he dealt with tragedy ... there were all these sorts of things I could I could see the story and so I just tried to power on in and make it as good a book as could.

BH: Writing By Writers co-founder and award-winning writer and teacher Pam Houston has also written extensively for magazines and newspapers, including dozens for the New York Times. She uses keen, personal observation as the foundation of her articles, short stories, and books.

Pam Houston: All my books have been largely autobiographical. It’s just what I do. It’s the way that I make work. I go out in the world then I pay really strict attention and I write down the things that I notice and then I combined them and recombine them and those turned into my stories and my novels, that’s how it’s always been.

BH: We chatted more about Pam’s writing, teaching, and her novel Contents May Have Shifted in her Davis, California home:

PH: There is almost always a character at the center of the work who resembles me a lot, that’s just how it happens. And so, when I was writing Contents which I understood to be a kind of collage of all these little glimmering objects I had picked up from moving through the world for a period of years and going to lots of different countries and trying to do sort of an investigation of the ways different people keep faith kind of, I didn’t know whether my publisher would want to call it a novel or a memoir, there is a certain amount of pressure for us all to write memoirs here in this moment of memoir love, this literary moment where memoirs are so popular ...

BH: Pausing for a brief side note - I just heard an excellent chat on writing memoirs specifically. Terry Gross on NPR’s Fresh Air interviewed Mary Karr whose memoirs include The Liars’ Club, Cherry, and Lit. I’ll have a link to that interview in our show notes. Here’s more from Pam:

PH: But on the other hand my publisher knows that I tend to shape stories and in that shaping they start to not resemble exactly what really happened and so usually my books are called fiction. So, I really didn’t know. I wrote the whole book without knowing what we would call it, whether we would call it a memoir or a novel. And in the end we decided to call it a novel more because of the climate that the book was born into than anything else.

BH: I find this terrifying and daunting. Beyond being thrown into the deep end of a pool, this strikes me as a 1 mile open water swim with no training. I’ve found in that, with my attempts at longer form prose, I need more guidance, more direction.

Pam contributed an essay, Corn Maze, to Jill Talbot’s book Metawritings: Toward a Theory of Nonfiction, and I asked about her perspective on these rigid lines of genre: of fiction vs non-fiction.

PH: My belief system on the subject is what Corn Maze is about and that’s that we are in this lifelong unrequited love affair with language. Because of its unrequited nature, because it won’t just sit still and mean for us, and meaning is always shifting, meaning occurs at the junction of code and context, we know that, the linguist taught us that, so even if I write a sentence right now it’s going to mean something different in an hour and it’s going to mean something different in five years and it might be unintelligible in a 100 years. So the idea that we can make language represent reality in any kind of complete or consistent way just is simply not true.

You know, if something really funny happens on the way home by the time you get home and tell your loved ones about it it’s already better, like you’ve already made it better, and everybody knows that. And the same thing is happening for a writer when a writer is crafting words, if not more so. So that is not to say we just throw the baby out with the bathwater, like that’s not to say oh, well, we shouldn’t or there aren’t certain genres in which we should actually try, you know, if I’m writing a travel piece about Italy I should try to represent Italy as accurately as I can because someone is going to decide whether they want to go to Italy or not.

However, to pretend, as some people are doing right now, that it’s one way or the other, that language can absolutely represent reality and if it didn’t for you in a particular incident you would lie, that’s much too simplified for me.

BH: But now you are working on a memoir?

PH: I am.

PH: So with any self-proclaimed memoir like early in the process you know that’s what you’re doing or that’s the intent so if, I don’t know, 80% to 85% of the previous work has been autobiographical then in writing this project where does the other 15% to 20%...

PH: Go?

BH: come from and originate from?

PH: Yeah, well, that’s an interesting question and I, you know, I would be able to say more about that when I have something closer to a solid draft. But so far I’m honestly seeing how much I can stick to what really happened, like I’m doing it as an intellectual exercise in a certain way or you know an emotional exercise, both, I’m doing it as a writing exercise, you know, given all this stuff I’ve said and given Corn Maze and given how I have joked and been serious about all this through the years, I thought well what if I really tried, what if I really tried to make language represent reality, like what if I didn’t think it was okay to shape the truth in ways I’ve had before and so far I think I have although I wouldn’t want anybody to hold me to that exactly, you know I’d have to really go look at the manuscript. But I’ve been sort of dutiful about trying to the best of my knowledge to get everything exactly just to see what would happen if I did, because I’ve never tried that before and I thought it might be interesting to see what happened. And if I don’t know something for sure I say it right in the text, you know, or I say maybe it was like this, maybe it was like this.

BH: Right, right.

PH: And you know ironically I’m trying to do this like right at the moment where my memory is completely failing, you know, because I’m 53, so that’s also sort of funny. When I could have remembered I didn’t. But we’ll see how it goes.

BH: My mind buzzing around thoughts of language’s limitations, I spoke with Writing By Writers Faculty Josh Weil, author of the New York Times Editor’s Choice novel, The Great Glass Sea, and collection of novellas, The New Valley, which won the Sue Kaufman Prize for First fiction from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. We chatted near Tomales Bay, north of San Francisco, as a small plane buzzed overhead.

You dedicate Great Glass Sea to your brother and the story features this incredible complex fraternal love between two brothers and I'm wondering as an only child and as a parent of two I- I I'm baffled by siblings but also intrigued by siblings what is it about family for you that that helps inform your writing?

Josh Weil: Family is very important to me. My brother in particular has been very important to me um all my life. I mean I write a lot about uh father son relationships as well um and about romantic relationships as well um but my brother uh he he's five years older than I am, in the novel they're twins. Like most everything I write it comes from a kernel of something in my life but then by the time it reaches the published page it so wildly different um so luckily he understands that … [laughter]

JW: It's a a pretty uh uh it's a dark and difficult look at fraternal relationships um but uh my brother is five years older than I am and my parents got divorced when I was 5 um and he in some ways took on the role of the father figure - although my dad is a great dad um and I have a great relationship with him he wasn't around on the day to day basis when I was growing up so my brother took that that role on a little bit. And then um and then that just morphed into a close friendship as we got older and there was a point in both of our lives uh when we were the most important person in each other lives um and what I wanted to deal with in that book was for me a very painful and difficult growth process and necessary process part of being an adult um was shifting from that young adult slash childhood relationship with my brother into one that included all the complexities of wives and children and other people when all of the sudden you're not the most important person in your siblings life, as it should be. It’d be a problem if it kinda were.

BH: Similar to Josh, family is a strong influence in Alan Heathcock’s fiction. Specifically that rite of passage from that somewhat carefree adult days to the murky unkowns of parenting. Alan teaches in the Boise State MFA Creative Writing program, and his recent collection of short stories, VOLT, was a “Best Book” selection from a literary who’s who: GQ, Publishers Weekly, and Salon.

Alan Heathcock: Your preoccupations as human being change when you become a parent because you become aware of the world that your children are walking around then, and it’s a constant thing, a constant interrogation of the world. I’m thinking about today, and what’s happening today with my children in the street we live in but then I think about the world at large. That couple with the fact that as you get older you begin to understand that the world is completely made by people; I mean we have weather and things like that too but in terms of how the world is run and what gets made and how we feel about ourselves, the stories that are told, it’s all people and it’s all stories,

BH: Yes, stories have this unique power to unite, to bond us …

AH: and a recognition that it’s my job to create the world that I want for my children to live into, and to also teach them that it’s their world and it’s their responsibility to put their story into the world as well. And I don’t mean that in any metaphysical way, I mean that in an actual literal way that the world is designed, you know, from religion to politics to commerce, all around, all of it is determined by stories, so my stories are completely informed by the fact that I have three children who I love dearly and I want the world to represent itself in a way where they can go into it with compassion and empathy and give love, feel love, and I know that sounds corny but I mean it.

BH: We’re going to wrap up soon. These are intended to be kind of stream of consciousness in terms of answers, so just a quick rapid fire … what writer dead or alive would you like to have a meal with?

AH: Cormac McCarthy.

BH: Here’s Gary Ferguson:

GF: John Steinbeck.

BH: And Josh Weil?

JW: What writer, dead or alive, would I like to have a meal with? Um, psh, probably W. G. Sebald

BH: Tom Barbash.

TB: Oh, that's a good one. I suppose Chekhov whose life is so varied and amazing and was such a beautiful human being. … Yeah I’d have a lot to say to him I think.

BH: and Pam Houston.

PH: I don’t see how - I’m not that quick. That seems like such an important question. If it was alive it would be Alice Munroe. And if were dead it would be Eudora Welty.

BH: And which writer, dead or alive, would YOU like to have a meal with? Let us know via Facebook.com/StoryGeometry, use the hashtag StoryGeo, I’m @BenHess Twitter or via email, hello@storygeometry.org. That does it for Episode Three: The Deep End and a special thank you to Tom Barbash, Gary Ferguson, Alan Heathcock and Josh Weil on sharing their perspectives on the craft of writing.

I, Ben Hess produced and edited the episode, and wholeheartedly approve endorse all comments herein. Our theme music is from the lovely Brit Mark Hodgkin, markhodgkin.com and our logo was designed by Thatcher Warrick Hess. As always, thanks to Writing by Writers, that’s writing x writers dot org where you can explore a myriad of 2016 workshop opportunities to further your own craft. We’ve just launched Story Geometry and need your subscriptions, reviews, and ratings in iTunes. And if you’re standing, you may want to sit down - Episode Four’s going to give a taste on the business side of writing featuring editor Jay Schaefer, agent Gordon Warnock, and more with award winning writers Tom Barbash, Pam Houston, and Josh Weil. Until then, take a leap into the literary waters and yell Story Geometry on the way in. Thanks for listening.